Philosophy of Freedom Study Group and Notes

If you are interested in covering all the chapters and forms of the Philosophy of

Freedom go to my Udemy.com course: $89 course discount coupon:

https://www.udemy.com/course/rudolf-steiners-philosophy-of-freedom-for-beginners/?couponCode=NEWTHINKING

code= NEWTHINKING

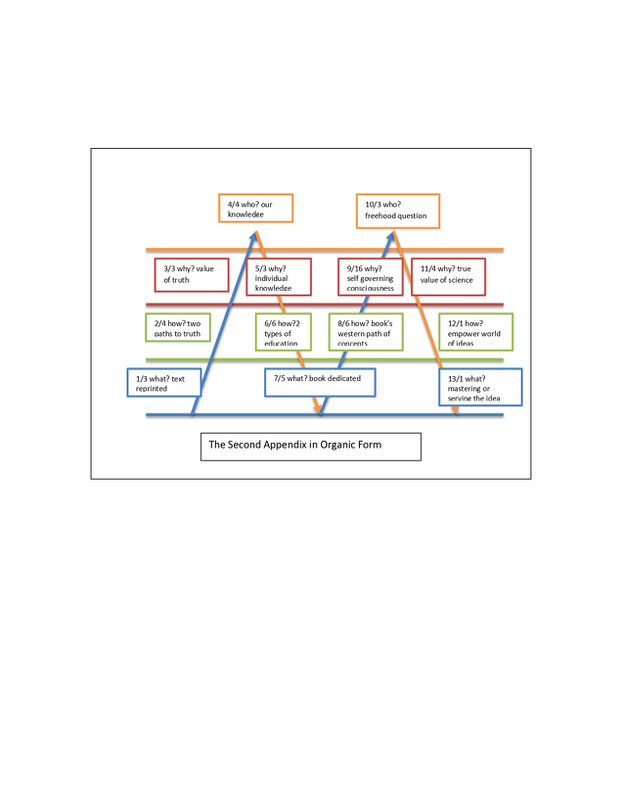

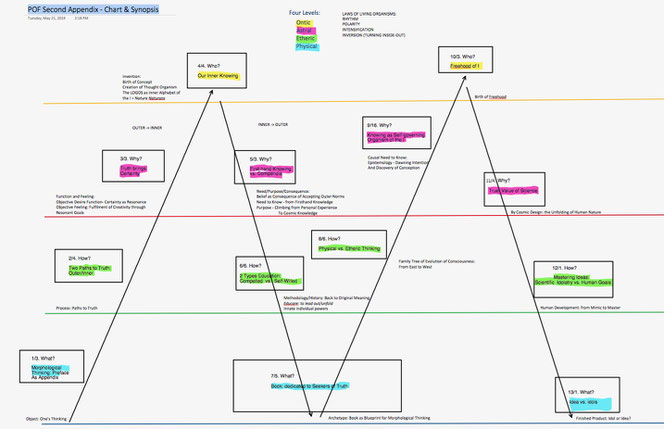

All Philosophy of Freedom Groups should start with a close reading of the Preface to the 1918 Revised Edition and The Second Appendix to the Philosophy of Freedom. These "prefaces" present how the book is to be read. They are unfortunately widely misread because they are not taken at face. There are few texts where Steiner is referencing his new thinking system, and they are not decipherable without a pre-knowledge of what organic thinking is.

In the Preface 1918, Steiner says the Philosophy

of Freedom is based on his view of the human being ( which we know can be 9-fold, 7-fold etc.). In fact, his first paragraph in the Preface 1918 has 9 sentences which

correspond to the members of the nine-fold human being as presented in his book Theosophy. Sounds amazing? Read it carefully and you shall

see for yourself!

In the first paragraph to the Second Appendix Steiner writes that he included the Appendix NOT because it added content, but because of its "thought-atmosphere" or better translated as a "way of thinking", or "thinking-vibe" in modern jargon. ("Gedanken-Stimmung" is atmosphere, mood, tuning, vibe, state of mind). Thus its 'content' is juxtaposed to a 'way of thinking', and to translate Stimmung into "mood" would make no sense philosophically as it sounds like he was sitting in a salon smoking and contemplating his book.

In essence, Steiner is saying that the Second Appendix should be read for its new way of thinking, for its thought-vibration, not simply for its contents. In the 8th paragraph of the Second Appendix Steiner says that the book's ideas have "contours" and "etheric" forms which the reader must meditate on in sense-free-thinking. Does this sound like a normal philosophy book?

In the fourth paragraph of the Preface 1918, Steiner writes that the reader can enter into spiritual experience "if one can enter into the style of the writing." When Steiner talks about the Philosophy of Freedom as the foundation for Anthroposophy, he is talking about the book's new thinking, not its new contents - since Steiner says clearly the book does not have any result of the sciences, nor results of spiritual science! Without results of sciences and of spiritual science, the book has therefore no results, and no content! Its true content is its living form.

In the 9th paragraph of the Second Appendix Steiner

writes "in the book the goal is a philosophical one: science shall itself become organic living." Where is there talk in the Philosophy of Freedom of making science organic-living?

There isn't!The book makes an organic science by training your mind to think in organic thought-forms.

Organic-living is how the book was written. The goal is to immerse yourself in the

structure of the book: both the human structure and goethean structure (rhythm, enhancement, polarity, and inversion) are identical in movement. To start your studies on the

Philosophy of Freedom, the best place is my booklet A Study Guide for Rudolf Steiner's Heart

Thinking where I cover the Preface 1918 and Second Appendix in detail, or my Youtube.com videos on heart thinking.

Chapter One Conscious Human Action

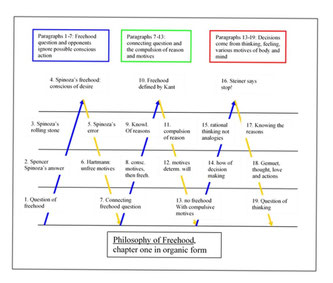

Rudolf Steiner's thought-form for the first four chapters are fun and relatively easy to master. Chapter One, Conscious Human Action, is fairly easy to condense and to find its parts. Below are my synopses/condensments. Click here for the text of chapter one which numbered according to the German original.

Chapter I, Conscious Human Action

1/14 What? Freedom question: Is the man free? Supports and detractors: D. Strauss freedom of choice is empty; Steiner there is a reason why one chooses an action.

2/10 How? Freedom opponents: Against freedom of choice: Spencer freedom of choice is negated; Spinoza: necessity of our nature and God’s nature is free necessity.

3/5 Why? Created beings determined: Spinoza: the stone is determined to roll by external cause.

4/6 Who? Spinoza’s definition of freedom: Human know he is striving and therefore thinks he is free: conscious of his desires but not causes: child and milk, knows the better and does the worst.

5/16 Why? Spinoza’s Error: Spinoza has a lack of power of discernment: motive of actions which I understand are not equal to organic process of desiring milk.

6/6 How? Hartmann’s character-disposition: will is determined by circumstances: or mental picture is made into motive based on character disposition. Spinoza’s error.

7/3 What? Additional questions: freedom of the will one-sided? Connected to other questions?

8/3 How? Question of conscious action: The question of the difference between a conscious and unconscious motive will be next.

9/3 Why? Knowledge of the reasons?: man divided into two parts the doer and the knower, but never the one acting out of knowledge.

10/2 Who? Kant’s definition of freedom: freedom is the dominion of reason, or life according to goals and decisions.

11/3 Why? Kant’s error: is reason determining too? Then freedom is an illusion!

12/2 How? Hamerling’s motive determines volition: man can do what he wills, but he cannot want what he wills, because his volition is determined by motives.

13/6 What? Are motives only compelling? Hamerling does not differentiate between conscious and unconscious motives. No freedom!

14/1 How? How decisions are made: not whether I can carry them out.

15/13 Why? Rational thinking: no animal analogies, and Paul Ree: the stone and the donkey – causality is invisible. Conscious motives?

16/1 Who? No notion of freedom: enough examples.

17/6 Why? Significance of thinking and Hegel: thinking gives man’s actions their unique character.

18/20 How? Actions arise from thinking, MP’s, motives, Gemuet, and love: The more idealistic the mental picture the more blessed is the love.

19/2 What? Final question: essence of human action must be preceded by the question of the origin of thinking.

VERY LOYAL to the Level Synopses:

Chapter One Philosophy of Freehood

1. What is one of the most important questions of life or science? – Is the HB free in his thinking and willing? Strong views on both sides for and against. Majority contemporary view (eg Strauss): Freehood can’t mean “free choice” b/c there’s always a reason.

2. How do opponents view the Q of freehood? Obviously the HB is not free (eg Spencer.) Seed of opposition in Spinoza: Even God is determined by “free necessity.”

3. Why opponents view HB as unfree? B/c for them, external forces determine all created things. (Spinoza’s rock.)

4. Who thinks otherwise? Everyone (according to Spinoza), who defines Freedom as: Knowing what I want. But Spinoza: HB is like a conscious rock: HB believes he’s free. Yes, the HB knows what he wants, but he is unconscious of causes.

5. Why is Spinoza mistaken in his view? B/c are all actions of the same kind? There’s a difference b/n actions that I know why I do them and those I don’t.

6. How does Von Hartmann view the Q of freehood? Characterological disposition, together with external causes, determines human willing.

7. What other question must necessarily be linked to the Q of freehood? (Can the Q of freehood be asked by itself?)

8. How then to answer the Q of freehood? First determine the difference b/n a conscious motive and a blind impulse for action.

9. Why hasn’t that Q of different actions been asked more often? B/c (in philosophy) the whole HB has been split into knower and doer; but the knowing-doer – who matters most – has been left out.

10. Who, for example, has left the knowing-doer out? Kant, who defines freehood as: acting under reason rather than animal desire.

11. Why are such assertions of freehood useless? B/c if reason compels in the same way as do primal desires, then freehood is an illusion.

12. How else is freehood defined? As doing what one wants. But Hamerling: That’s absurd: to want w/o wanting is wanting w/o reason. But the concept of motive is necessarily always linked to the concept of desire.

13. What is the point for the question of freehood if reason compels? There is none. Ask: Are there only motives that compel?

14. How does the decision arise in me? That’s the main point. Not: Can I carry out a decision once made.

15. Why are animal analogies (e.g. Ree’s donkey) useless? B/c the HB is not merely an animal; in his thinking he is distinct from the all other living beings.

16. Who else thinks the HB is not free? Enough examples that prove opponents of freehood don’t know what freehood is.

17. Why don’t people know what freehood is? B/c a concept of knowing about anything is not possible w/o knowledge of the origin and significance of thinking. Hegel: HB is not like an animal: “w/thinking the soul becomes spirit.”

18. How about feelings, how do they arise? Like willing, also feelings proceed from thinking: “The thought is father to the feeling.”

19. What is the conclusion? The question of freehood presumes the Q of the origin of thinking. So, that next.

Chapter Two The Fundamental Desire for Knowledge

Chapter Two is also pretty straight forward. As you are reading, you will notice the obvious symmetry in the chapter. Particular to this chapter are the wings, which work as parenthetical remarks to the main body of the text. Wings usually means this form has special significance.

In this chapter, Steiner states that ordinary human consciousness can penetrate what the book is offering. Why do academics

try to present Steiner as an academic? Well, academics did not know that the form of the book is where the knowledge is, not in its content! This book is for the "concept artist" who is a true

philosopher, and is not for today's academics who write theoretical treatises on Steiner's work. Steiner said in his Preface 1918: "not a theoretical answer will be given" but "the question will

be answer livingly anew."

Click Here for a copy of a numbered Chapter Two.

Chapter II,

The Fundamental Desire for Knowledge

1/1 Wing? Two Souls: Two souls one holds fast in lust to the world, the other rises from the gloom to lofty fields.

2/19 What? Human nature and questions: Goethe expresses a feature of human nature which is his desire to know and unsatisfied with observation, the human being asks questions underlying experience of nature e.g., a tree, the egg in heredity.

3/3 How? We split I and world: Our seeking to know what lies beyond observation makes us conscious of our antithesis to the world: the universe appears as I and the World.

4/2 Why? Feeling of belonging: we erect this barrier with the dawning of consciousness and we still feel ourselves to be beings that are within the universe.

5/27 How? Bridging anti-thesis thru academics (monist and dualist) : Feeling of separation makes us want to bridge this antithesis through art, science, and religion and unity is given when world content becomes thought content. Dualism’s vain struggle to reconcile opposites of spirit and matter, thus his ego remains spirit and objects in the world of matter. Human being must rediscover riddle of matter and the riddle of his own nature. Monism erases the opposites even though they are present. Dualism sees to fundamentally different entities the three forms of monism.

6/15 What? The Materialist: The materialist begins with a thought of matter and regards them as purely material processes e.g., thinking takes place in the brain has a mechanical effect he meets the same riddle because he ascribes thinking to matter and not to his “I”.

7/14 How? The Spiritualist: The spiritualist denies matter, places the I inside of spirit and can’t access the material world. The material world becomes a closed book to the ego it’s actions and experience e.g., Fichte.

8/4 Why? One-sided idealism: When the human being reflects upon his I, he acknowledges the world of ideas and mistakes it for the spiritual world.

9/5 how? Idealist variant: Thinking is the product of the material and the material is the product of the thinking which is the equivalent of Munchhausen’s pigtail.

10/3 What? The Atomist: The third form of monism is atomism where the question is shifted from our consciousness to the duality of the atom.

11/5 How? Goethe on Bridging: nature is in us, we are in her.

12/2 Why? Feel nature’s pulse: Although we are estranged from nature, we fell her pulsating in us.

13/12 How? Find the rescued elements: The way back to nature is to connect to her within us, to find her elements recused from the flight.

14/2 What? Something more than I: investigation of our own being. Something more than I.

15/6 Wing? Experience of consciousness: discussion not scientific, nomenclature not used in precise manner. Concern is the way we experience consciousness.

Chapter III, Thinking in the Service of Knowing the World

Some Notes on Chapter 3:

If you were looking at O'Neil's Workbook to the Philosophy of Spiritual Activity, then you will notice that this form has been changed. Originally O'Neil gave the chapter a form with wings but it now stands as 4 eight-forms. There are two main movements: there is an intensification for each group of eight paragraphs from physical to ego level, plus a mirroring from the outside into the middle. Meditating this form requires some real muscles as one begins to immerse oneself in a dream of 32 paragraphs.

Click here for a copy of the chapter 3 and some study notes to help you feel into its content and form.

1) Let us look at the chapter from the point of view of COLOR:

First look at the two halves: (make synopses of the each half)

Paragraph of 1 thru 16 Paragraphs 17 thru 32

2) Look at the four main parts: (Make synopses of each fourth)

Paragraphs 1 thru 8 Paragraph 9 thru 16 Paragraph 17 thru 24 Paragraph 25 thru 32

3) Look at the eight main parts: (Make synopses of each eight)

Para 1-4 Para 5-8 Para 9-12 Para 13-16 Para 17-20 Para 21-24 Para 25-28 Para 29-32

4) When you are presenting the paragraphs, speak each paragraph in a different tone:

Physical level: speak clear, slow, form, grounding,

Etheric level: speak in a lively manner, staccato, quickly,

Astral Level: Speak carefully, antipathy. sympathy, impassioned, weary,

I-Level: Speak clearly, conclusively, with careful insight, revelatory, emphatic

Philosophy of Freedom Ch. 3 summaries

w 1/11: To an external process independent of me, such as collision of billiard balls, I can add a conceptual process that does depend on me.

h 2/7: Whether this process is voluntary or determined, we feel drawn to drawn to execute it. What do we gain by finding the conceptual counterpart to an external process?

wh 3/8: In the case of billiard balls, we gain an understanding of how the events in the external process are connected. This happens only if observation is linked to thinking.

o 4/4: Observation and thinking are foundational for all other human spiritual activity.

o 5/6: Whether thinking matters to the origin of phenomena, it is important to any understanding or discussion of them.

wh 6/4: On its side, observation is necessary because we are organized so that it is the only way for us to come in contact with objects.

h 7/5: Observation is how we first become aware of anything in our consciousness, including thoughts and feelings.

w 8/8: As an object of observation, thinking differs from all else because we do not normally observe what we think while we observe objects.

w 9/14: Feelings about an object are different from concepts born of thinking because they occur without my conscious activity and they tell me something about myself, in contrast to concepts about the object.

h 10/9: Thinking differs from other spiritual activities in that it is directed to the object of observation, and not to the thinker.

wh 11/2: What normally concerns us is not thinking but the object of thinking.

o 12/1: Thinking is the unobserved element in normal spiritual life.

ol 13/7: This is because thinking is our own activity, performed as we observe what is given to observation.

wh 14/7: I cannot observe my own present thinking; I can only observe what I have thought in the past.

h 15/5: Thinking must already be there in order for us to observe it, as God observed the world on the 7th day after 6 days of creation.

w 16/6: Because we produce our thinking, we know its connections completely.

w 17/15: Thinking as we mean it here is not a physiological process. Those who cannot look past the physical will not understand.

h 18/5: Everyone of good will can observe their thinking, and thereby witness a process of which they understand every step and connection – a secure point of knowledge.

wh 19/18: Descartes said, “I think therefore I am,” because he experienced this and saw that it demonstrates the existence of the person who produces the thinking.

o 20/9: In normal awareness, an unobserved element hovers in the background: thinking. When we observe past thinking, this is the same activity as the present thinking that observes it, and so there is no unobserved element in the process.

o 21/6: We may wonder if it is justified to add to an outside object with our thinking, but there is no such issue with our thinking itself.

wh 22/6: Schelling’s “To know nature is to create nature” is impossible since to create nature we would first have to know it, or else we would create a nature foreign to the one we have.

h 23/5: But we can, indeed do, create thinking before we know it, because we ourselves bring it into existence.

w 24/5: One say the same is true of digestion or some other activity, but one cannot digest digestion as one can think about thinking.

w 25/5: Outer things are puzzling because I have no part in their creation, but with thinking I have a part of the world process that I myself perform.

h 26/4: There is a widespread error that says the preconscious thinking we do when observing objects is not the same as the thinking we seem to find when we contemplate our activity.

wh 27/9: But I do not make thinking into something else by contemplating it with thinking. I can only say I do not know what the thinking of another being is in itself.

o 28/3: Since I contemplate the rest of the world with my thinking, there is no reason to contemplate thinking itself any differently than with my thinking.

o 29/7: In thinking, we have a principle of understanding that supports itself, like the fulcrum Archimedes would have needed in order to lift the world with a lever.

wh 30/14: Although thinking is a product of human consciousness, we begin with the former because it is necessary in order to understand the latter.

h 31/11: We start with thinking in complete neutrality because of all things in the world process it is closest to us.

w 32/7: It is invalid to object that we cannot know whether thinking is correct, because thinking is a fact.

Here is the amazing chapter 3.

Chapter III, Thinking in the Service

of Knowing the World

1/11 What? The Billiard balls: I observe the communicated movement of billiard balls without my influence until I reflect, that is, the conceptual process because objects don’t come with concepts: what do we gain thereby?

2/7 How? My activity in conceptual process: our activity? This activity seems to be mine, (vs, Ziehen), and I am active in the conceptual process because objects don’t come with concepts: what do we gain thereby?

3/8 Why? The difference with the right concept: There is a profound difference after discovering the right concept, since I can, with blocked vision, know the course of the balls when thinking and observing are combined.

4/4 Who? Points of departure: observation and thinking Observation and thinking are the points of departure for the entire intellectual striving of humanity in science and philosophy.

5/6 Who? Thinking presupposed in other principles: Principles must be observed and expressed in clear thoughts and thus the philosopher admits that thinking presupposes his activity and whether thinking is the main element in world evolution will not be decided.

6/4 Why? Observation necessary for objects: Observation is necessary for knowledge of objects, just as thinking is for concepts, because thinking doesn’t create the objects.

7/5 How? We observe other soul activities: Observation precedes thinking, we use observation for awareness of content of the role of thinking in concept formation, sensation, dreams, feeling, acts of will, illusions, and ideas.

8/8 What? Thinking as Object: Thinking as an object of observation differs: I must take a standpoint outside of myself if I observe my thinking about a table or tree which is an exceptional state.

9/14 What? Objection: feeling kindled by object: Objection: feeling is also kindled by an object: pleasure however is not the same as my concept formation: feeling characterizes me not the object.

10/8 How? Thinking focused solely on Object: All activities of the soul are objects of observation because thinking in its peculiar nature is concentrated solely on the object not on the thinking personality and in the case of the table I do not enter into a relationship with it.

11/2 Why? Thinker forgets thinking: The peculiar nature is also that the thinker forgets he is thinking during the activity since he is occupied by the object not the process.

12/1 Who? Unobserved element: the first observation is that thinking the unobserved element of our normal mental life.

13/7 Who? Thinking Contemplation on objects: The reason it is unobserved is because it depends on my activity which in thinking contemplation is occupied with the objects given in the world, not the activity of my own thinking.

14/7 Why? Split myself to observe present thinking: In the exceptional state I cannot observe my present thinking without splitting myself into two, even if I make notes about some one else’s thinking.

15/5 How? Activity and contemplation: Incompatible are productive activity and contemplation of it analog to the Book of Moses is our thinking and its contemplation.

16/6 What? Knowing Thinking: The same reason for the impossibility counts for the reason we know it most intimately we know thinking’s course and even conceptual connections directly.

17/15 What? Observing thinking without materialism: Steiner is speaking about thinking without reference to the material process and the materialistic age still talks like Cabanis, and thus needs to transcend it in order to grasp it.

18/5 How? Firm point for explaining: Every good-willed person can observe thinking and know what he creates – a firm point for explaining other phenomenon.

19/18 Why? Feeling of certainty: Descartes feeling of certainty comes from our bringing it forth: the sense of thinking’s existence is derived out of itself.

20/9 Who? Nothing neglected When we make thinking an object of observation, I have no neglected element because the object is qualitatively the same as the activity directed on it.

21/6 Who? Weaving an Object? What if I weave an object into my thinking? No foreign element if I reflect on my own process and no need to justify it.

22/6 Why? To know is to create: TO know nature means to create holds good only for an uncreated nature.

23/5 How? Achieved in Thinking: We achieve, creating before knowing, in our thinking unlike other objects of observation.

24/5 What? Digestion equal to thinking?: Digestion, or I walk therefore I am, cannot be compared because digestion cannot become the object of digestion.

25/ What? Tip of the world process: In thinking, we have grasped the tip of the world process, and have a primal starting point for studying all things.

26/4 How? Error! Weaving in objects: A widespread error is that the thinking we consciously extract from the weaving of objects is not the same as the one unconsciously woven into the objects.

27/9 Why? Escape thinking is impossible: The mistaken ones don’t know that it is impossible to escape thinking by studying it nor do I alter it by thinking about it and I can imagine a being with a different sense organ has different mental picture of a horse, but its my thinking and not another’s.

28/3 Who? No reason: my standpoint: There is no reason to view my thinking from another standpoint.

29/7 Who? Knowing other things? Archimedes: Steiner believes there are sufficient reasons for having thinking as our starting point like Archimedes level in that we know thinking through thinking, what else can we know?

30/14 Why? Consciousness before thinking? The question of consciousness coming before thinking is answered by the fact we use thinking to understand the relationship and the philosopher needs a sound foundation for objects in front of him.

31/11 How? Last is First: Thinking must be understood first, the last as first, geology example the last in evolution is thinking.

32/7 What? Applying thinking? The goal of the book is to show the right of wrongness of applying thinking to the world is a fact.

If you are looking for the other chapters, let me know and I will post them!

Preface to the Revised 1918 Edition

1/9 What?

1. Two root-questions of the human soul-life are the focal point, toward which everything is directed that will be discussed in this book.

2. The first question is whether it is possible to view the human being in such a way

that this view proves itself to be the support for everything else which comes to meet the human being, through experience or science, and which gives him the feeling that it could not support itself.

3. Thereby one could easily be driven by doubt and critical judgment into the realm of uncertainty.

4. The other question is this: can the human being as a being of will claim free will for himself, or is such freehood a mere illusion, which arises in him because he is not aware of the workings of necessity on which, as any other natural event, his will depends?

5. No artificial spinning of thoughts calls this question forth.

6. It comes to the soul quite naturally in a particular state of the soul.

7. And one can feel that something in the soul would decline, from what it should be,

if it did not for once confront with the mightiest possible earnest questioning the two possibilities: freehood or necessity of will.

8. In this book it will be shown that the soul-experiences, which the human being must discover through the second question, depend upon which point of view he is able to take toward the first.

9. The attempt is made to prove that there is a certain view of the human being which can support his other knowledge; and furthermore, to point out that with this view a justification is won for the idea of freehood of will, if only that soul-region is first found in which free will can unfold itself.

2/5 How?

1. The view, which is under discussion here in reference to these two questions, presents itself as one that, once attained, can be integrated as a member of the truly living soul life.

2. There is no theoretical answer given that, once acquired, can be carried about as a conviction merely preserved in the memory.

3. This kind of answer would be only an illusory one for the type of thinking, which is the foundation of this book.

4. Not such a finished, fixed answer is given, rather a definite region of soul-experience is referred to, in which one may, through the inner activity of the soul itself, answer the question livingly anew at any moment he requires.

5. The true view of this region will give the one who eventually finds the soul-sphere where these questions unfold that which he needs for these two riddles of life, so that he may, so empowered, enter further into the widths and depths of this enigmatic human life, into which need and destiny impel him to wander.

3/1 Why?

1. - A kind of knowledge seems thereby to be pointed to which, through its own inner life and by the connectedness of this inner life to the whole life of the human soul, proves its validity and usefulness.

4/10 Why?

1. This is what I thought about the content of the book when I wrote it down twenty-five years ago.

2. Today, too, I have to write down such sentences if I want to characterize the purpose of the thoughts of this book.

3. At the original writing I limited myself to say no more than that, which in the utmost closest sense is connected with the two basic questions, referred to here.

4. If someone should be amazed that he finds in the book no reference to that region of the world of spiritual experience which came to expression in my later writings, he should bear in mind that in those days I did not however want to give a description of results of spiritual research but I wanted to build first the foundation on which such results could rest.

5. This Philosophy of Freehood does not contain any such specific spiritual results any more than it contains specific results of other fields of knowledge; but he who strives to attain certainty for such cognition cannot, in my view, ignore that which it does indeed contain.

6. What is said in the book can be acceptable to anyone who, for whatever reasons of his own, does not want anything to do with the results of my spiritual scientific research.

7. To the one, however, who can regard these spiritual scientific results, as something toward which he is attracted, what has been attempted here will also be important.

8. It is this: to prove how an open-minded consideration of these two questions which are fundamental for all knowing, leads to the view that the human being lives in a true spiritual world.

9. In this book the attempt is made to justify cognition of the spiritual world before entering into actual spiritual experience.

10. And this justification is so undertaken that in these chapters one need not look at my later valid experiences in order to find acceptable what is said here, if one is able or wants to enter into the particular style of the writing itself.

5/5 How?

1. Thus it seems to me that this book on the one hand assumes a position completely independent of my actual spiritual scientific writings; yet on the other hand it also stands in the closest possible connection to them.

2. These considerations brought me now, after twenty-five years, to republish the content of the text almost completely unchanged in all essentials.

3. I have only made somewhat longer additions to a number of sections.

4. The experiences I made with the incorrect interpretations of what I said caused me to publish comprehensive commentaries.

5. I changed only those places where what I said a quarter of a century ago seemed to me inappropriately formulated for the present time.

(Only a person wanting to discredit me could find occasion on the basis of the changes made in this way, to say that I have changed my fundamental conviction.)

6/6 What?

1. The book has been sold out for many years.

2. I nevertheless hesitated for a long time with the completion of this new edition and it seems to me, in following the line of thought in the previous section, that today the same should be expressed which I asserted twenty-five years ago in reference to these questions.

3. I have asked myself again and again whether I might not discuss several topics of the numerous contemporary philosophical views put forward since the publication of the first edition.

4. To do this in a way acceptable to me was impossible in recent times because of the demands of my pure spiritual scientific research.

5. Yet I have convinced myself now after a most intense review of present day philosophical work that as tempting as such a discussion in itself would be, it is for what should be said through my book, not to be included in the same.

6. What seemed to me necessary to say, from the point of view of the Philosophy of Freehood about the most recent philosophical directions can be found in the second volume of my Riddles of Philosophy.

April 1918 Rudolf Steiner

The Second Appendix to the Philosophy of Freedom

1/3

1. In what follows will be reproduced in all its essentials that which stood as a kind of “preface” in the first edition of this book.

2. I placed it here as an “appendix,” since it reflects the type of thinking in which I wrote it twenty-five years ago, and not because it adds to the content of the book.

3. I did not want to leave it out completely for the simple reason, that time and again the opinion surfaces that I have something to suppress of my earlier writings because of my later spiritual writings.

2/4

1. Our age can only want to draw truth out of the depths of man’s being. *

2. Of Schiller’s well-known two paths:

“Truth seek we both, you in outer life, I within

In the heart, and each will find it for sure.

Is the eye healthy so it meets the Creator outside;

Is the heart healthy then it reflects inwardly the World”

the present age will benefit more from the second.

3. A truth that comes to us from the outside always carries the stamp of uncertainty.

4. Only what appears as truth to each and every one of us in his own inner being is what we want to believe.

* Footnote: Only the first introductory paragraphs have been completely omitted from this work, which today appear to me totally unessential. What is said in the remaining paragraphs, however, seems to me necessary to say in the present because of and in spite of the natural scientific manner of thinking of our contemporaries.

3/3

1. Only truth can bring us certainty in the development of our individual powers.

2. Whoever is tormented by doubt his powers are lamed.

3. In a world that is puzzling to him he can find no goal for his creativity.

4/4

1. We no longer want merely to believe; we want to know.

2. Belief requires the accepting of truths, which we cannot fully grasp.

3. However, what we do not fully grasp undermines our individuality, which wants to experience everything with its deepest inner being.

4. Only that knowing satisfies us that subjects itself to no external norms, but springs instead out of the inner life of the personality.

5/3

1. We also do not want a form of knowing, which is fixed for all eternity in rigid academic rules and is kept in compendia valid for all time.

2. We hold that each of us is justified in starting from firsthand experiences, from immediate life conditions, and from there climbing to a knowledge of the whole universe.

3. We strive for certainty in knowing, but each in his own unique way.

6/6

1. Our scientific theories should also no longer take the position that our acceptance of

them was a matter of absolute coercion.

2. None of us would give a title to an academic work such as Fichte once did: “A Crystal-Clear Report to the Public at Large on the Actual Nature of Modern Philosophy.

3. An Attempt to Compel Readers to Understand.”

4. Today nobody should be compelled to understand.

5. We are not asking for acceptance or agreement from anyone who is not driven by a specific need to form his own personal worldview.

6. Nowadays we also do not want to cram knowledge into the unripe human being, the child, instead we try to develop his faculties so that he will not have to be compelled to understand but will want to understand.

7/5

1. I am under no illusion in regard to this characteristic of my time.

2. I know that generic mass-ified culture [individualitaetloses Schablonentum] lives and spreads itself throughout society.

3. But I know just as well that many of my contemporaries seek to set up their lives according to the direction indicated here.

4. To them I want to dedicate this work.

5. It should not lead down “the only possible” path to truth, but it should tell about the path one has taken, for whom truth is what it is all about.

8/6

1. The book leads at first into more abstract spheres where thought must take on sharp contours in order to come to certain points.

2. However, the reader will be led out of these dry concepts and into concrete life.

3. I am certainly of the opinion that one must lift oneself into the ether world of concepts, if one wants to penetrate existence in all directions.

4. He who only knows how to have pleasure through his senses, doesn’t know life’s finest pleasures.

5. The eastern masters have their disciples spend years in a life of renunciation and asceticism before they disclose to them what they themselves know.

6. The West no longer requires pious practices and ascetic exercises for scientific knowledge, but what is needed instead is the good will that leads to withdrawing oneself for short periods of time from the firsthand impressions of life and entering into the spheres of the pure thought world.

9/16

1. There are many realms of life.

2. Every single one has developed a particular science for itself.

3. Life itself, however, is a unity and the more the sciences* are striving to research in their own specialized areas the more they distance themselves from the view of the living unity of the world.

4. There must be a type of knowing that seeks in the specialized ‘sciences’ that which is necessary to lead us back once more to the wholeness of life.

5. The specialized researcher wants through his own knowledge to gain an understanding of the world and its workings; in this book the goal is a philosophical one: science shall itself become organic-living.

6. The specialized sciences are preliminary stages of the science striven for here.

7. A similar relationship predominates in the arts.

8. The composer works on the basis of the theory of composition.

9. The latter is the sum of knowledge whose possession is a necessary precondition of composing.

10. In composing, the laws of the theory of composition serve life itself, serve actual reality.

11. In exactly the same sense, philosophy is a creative art.

12. All genuine philosophers are concept-artists.

13. Through them, human ideas have become artistic materials and the scientific method

have become artistic technique.

14. Thereby, abstract thinking gains concrete, individual life.

15. Ideas become life-powers.

16. We have then not just a knowing about things, but we have made Knowing instead into an actual, self-governing organism; our authentic, active consciousness has placed itself above a mere passive receiving of truths.

10/3

1. How philosophy as art relates to the freehood of the human being, what freehood is, and whether we are active in our freehood or able to become active: this is the main question of my book.

2. All other scientific explanations are included here only because they provide an explanation, in my opinion, about those things that are of importance to human beings.

3. A “Philosophy of Freehood” shall be given in these pages.

11/4

1. All scientific endeavors would be only a satisfying of idle curiosity, if they did not strive toward uplifting the existential worth of the human personality.

2. The sciences attain their true value only by demonstrating the human significance of their results.

3. Not the refinement of any single capacity of soul can be the final goal of individuality, but rather the development of all the faculties slumbering within us.

4. Knowledge only has value when it contributes to the all-sided unfolding of the whole human nature.

12/1

1. This book, therefore, conceives the relationship between scientific knowledge and life not in such a way that man has to bow down before the idea and consecrate his forces to its service, but rather in the sense that the human being masters the world of ideas in order to make use of it for his human goals, which transcend the mere scientific.

13/1

1. One must be able to experience and place oneself consciously above the idea; otherwise one falls into its servitude.

Zweiter Anhang (Die Philosophie Der Freiheit)

Absatz 1/3

1. In dem Folgenden wird in allem Wesentlichen wiedergegeben, was als eine Art «Vorrede» in der ersten Auflage dieses Buches stand.

2. 2. Da es mehr die Gedankenstimmung gibt, aus der ich vor fünfundzwanzig Jahren das Buch niederschrieb, als daß es mit dem Inhalte desselben unmittelbar etwas zu tun hätte, setze ich es hier als «Anhang» her.

3. Ganz weglassen möchte ich es aus dem Grunde nicht, weil immer wieder die Ansicht auftaucht, ich habe wegen meiner späteren geisteswissenschaftlichen Schriften etwas von meinen früheren Schriften zu unterdrücken.

Absatz 2/4

1. Unser Zeitalter kann die Wahrheit nur aus der Tiefe des menschlichen Wesens schöpfen wollen.*

2. Von Schillers bekannten zwei Wegen:

«Wahrheit suchen wir beide, du außen im Leben, ich innen

In dem Herzen, und so findet sie jeder gewiß.

Ist das Auge gesund, so begegnet es außen dem Schöpfer;

Ist es das Herz, dann gewiß spiegelt es innen die Welt»

wird der Gegenwart vorzüglich der zweite frommen.

3. Eine Wahrheit, die uns von außen kommt, trägt immer den Stempel der Unsicherheit an sich.

4. Nur was einem jeden von uns in seinem eigenen Innern als Wahrheit erscheint, daran mögen wir glauben.

Absatz 3/3

1. Nur die Wahrheit kann uns Sicherheit bringen im Entwickeln unserer individuellen Kräfte.

2. Wer von Zweifeln gequält ist, dessen Kräfte sind gelähmt.

3. In einer Welt, die ihm rätselhaft ist, kann er kein Ziel seines Schaffens finden.

Absatz 4/4

1. Wir wollen nicht mehr bloß glauben; wir wollen wissen.

2. Der Glaube fordert Anerkennung von Wahrheiten, die wir nicht ganz durchschauen.

3. Was wir aber nicht ganz durchschauen, widerstrebt dem Individuellen, das alles mit seinem tiefsten Innern durchleben will.

4. Nur das Wissen befriedigt uns, das keiner äußeren Norm sich unterwirft, sondern aus dem Innenleben der Persönlichkeit entspringt.

Absatz 5/3

1. Wir wollen auch kein solches Wissen, das in eingefrorenen Schulregeln sich ein für allemal ausgestaltet hat, und in für alle Zeiten gültigen Kompendien aufbewahrt ist.

2. Wir halten uns jeder berechtigt, von seinen nächsten Erfahrungen, seinen unmittelbaren Erlebnissen auszugehen, und von da aus zur Erkenntnis des ganzen Universums aufzusteigen.

3. Wir erstreben ein sicheres Wissen, aber jeder auf seine eigene Art.

Absatz 6/6

1. Unsere wissenschaftlichen Lehren sollen auch nicht mehr eine solche Gestalt annehmen, als wenn ihre Anerkennung Sache eines unbedingten Zwanges wäre.

2. Keiner von uns möchte einer wissenschaftlichen Schrift einen Titel geben, wie einst Fichte: «Sonnenklarer Bericht an das größere Publikum über das eigentliche Wesen der neuesten Philosophie. Ein Versuch, die Leser zum Verstehen zu zwingen.»

3. Heute soll niemand zum Verstehen gezwungen werden.

4. Wen nicht ein besonderes, individuelles Bedürfnis zu einer Anschauung treibt, von dem fordern wir keine Anerkennung, noch Zustimmung.

5. Auch dem noch unreifen Menschen, dem Kinde, wollen wir gegenwärtig keine Erkenntnisse eintrichtern, sondern wir suchen seine Fähigkeiten zu entwickeln, damit es nicht mehr zum Verstehen gezwungen zu werden braucht, sondern verstehen will.

Absatz 7/5

1. Ich gebe mich keiner Illusion hin in bezug auf diese Charakteristik meines Zeitalters.

2. Ich weiß, wie viel individualitätloses Schablonentum lebt und sich breit macht.

3. Aber ich weiß ebenso gut, daß viele meiner Zeitgenossen im Sinne der angedeuteten Richtung ihr Leben einzurichten suchen.

4. Ihnen möchte ich diese Schrift widmen.

5. Sie soll nicht «den einzig möglichen» Weg zur Wahrheit führen, aber sie soll von demjenigen erzählen, den einer eingeschlagen hat, dem es um Wahrheit zu tun ist.

Absatz 8/6

1. Die Schrift führt zuerst in abstraktere Gebiete, wo der Gedanke scharfe Konturen ziehen muß, um zu sichern Punkten zu kommen.

2. Aber der Leser wird aus den dürren Begriffen heraus auch in das konkrete Leben geführt.

3. Ich bin eben durchaus der Ansicht, daß man auch in das Ätherreich der Begriffe sich erheben muß, wenn man das Dasein nach allen Richtungen durchleben will.

4. Wer nur mit den Sinnen zu genießen versteht, der kennt die Leckerbissen des Lebens nicht.

5. Die orientalischen Gelehrten lassen die Lernenden erst Jahre eines entsagenden und asketischen Lebens verbringen, bevor sie ihnen mitteilen, was sie selbst wissen.

6. Das Abendland fordert zur Wissenschaft keine frommen Übungen und keine Askese mehr, aber es verlangt dafür den guten Willen, kurze Zeit sich den unmittelbaren Eindrücken des Lebens zu entziehen, und in das Gebiet der reinen Gedankenwelt sich zu begeben.

Absatz 9/16

1. Der Gebiete des Lebens sind viele.

2. Für jedes einzelne entwickeln sich besondere Wissenschaften.

3. Das Leben selbst aber ist eine Einheit, und je mehr die Wissenschaften be strebt sind, sich in die einzelnen Gebiete zu vertiefen, desto mehr entfernen sie sich von der Anschauung des lebendigen Weltganzen.

4. Es muß ein Wissen geben, das in den einzelnen Wissenschaften die Elemente sucht, um den Menschen zum vollen Leben wieder zurückzuführen.

5. Der wissenschaftliche Spezialforscher will sich durch seine Erkenntnisse ein Bewußtsein von der Welt und ihren Wirkungen erwerben; in dieser Schrift ist das Ziel ein philosophisches: die Wissenschaft soll selbst organisch-lebendig werden.

6. Die Einzelwissenschaften sind Vorstufen der hier angestrebten Wissenschaft.

7. Ein ähnliches Verhältnis herrscht in den Künsten.

8. Der Komponist arbeitet auf Grund der Kompositionslehre.

9. Die letztere ist eine Summe von Kenntnissen, deren Besitz eine notwendige Vorbedingung des Komponierens ist.

10. Im Komponieren dienen die Gesetze der Kompositionslehre dem Leben, der realen Wirklichkeit.

11. Genau in demselben Sinne ist die Philosophie eine Kunst.

12. Alle wirklichen Philosophen waren Begriffskünstler.

13. Für sie wurden die menschlichen Ideen zum Kunstmateriale und die wissenschaftliche Methode zur künstlerischen Technik.

14. Das abstrakte Denken gewinnt dadurch konkretes, individuelles Leben.

15. Die Ideen werden Lebensmächte.

16. Wir haben dann nicht bloß ein Wissen von den Dingen, sondern wir haben das Wissen zum realen, sich selbst beherrschenden Organismus gemacht; unser wirkliches, tätiges Bewußtsein hat sich über ein bloß passives Aufnehmen von Wahrheiten gestellt.

Absatz 10/3

1. Wie sich die Philosophie als Kunst zur Freiheit des Menschen verhält, was die letztere ist, und ob wir ihrer teilhaftig sind oder es werden können: das ist die Hauptfrage meiner Schrift.

2. Alle anderen wissenschaftlichen Ausführungen stehen hier nur, weil sie zuletzt Aufklärung geben über jene, meiner Meinung nach, den Menschen am nächsten liegenden Fragen.

3. Eine «Philosophie der Freiheit» soll in diesen Blättern gegeben werden.

Absatz 11/4

1. Alle Wissenschaft wäre nur Befriedigung müßiger Neugierde, wenn sie nicht auf die Erhöhung des Daseinswertes der menschlichen Persönlichkeit hinstrebte.

2. Den wahren Wert erhalten die Wissenschaften erst durch eine Darstellung der menschlichen Bedeutung ihrer Resultate.

3. Nicht die Veredlung eines einzelnen Seelenvermögens kann Endzweck des Individuums sein, sondern die Entwickelung aller in uns schlummernden Fähigkeiten.

4. Das Wissen hat nur dadurch Wert, daß es einen Beitrag liefert zur allseitigen Entfaltung der ganzen Menschennatur.

Absatz 12/1

1. Diese Schrift faßt deshalb die Beziehung zwischen Wissenschaft und Leben nicht so auf, daß der Mensch sich der Idee zu beugen hat und seine Kräfte ihrem Dienst weihen soll, sondern in dem Sinne, daß er sich der Ideenwelt bemächtigt, um sie zu seinen menschlichen Zielen, die über die bloß wissenschaftlichen hinausgehen, zu gebrauchen.

Absatz 13/1

1. Man muß sich der Idee erlebend gegenüberstellen können; sonst gerät man unter ihre Knechtschaft.

* Ganz weggelassen sind hier nur die allerersten Eingangssätze (der ersten Auflage) dieser Ausführungen, die mir heute ganz unwesentlich erscheinen. Was aber des weiteren darin gesagt ist, scheint mir auch gegenwärtig trotz der naturwissenschaftlichen Denkart unserer Zeitgenossen, ja gerade wegen derselben, zu sagen notwendig.

The original two paragraphs from the first edition that Steiner omitted from the original Appendix text entitled The Goals of all Knowledge:

1. I believe one of the fundamental characteristics of our age is that human interest centers in the cultus of individuality.

2. An energetic effort is being made to shake off every kind of authority.

3. Nothing is accepted as valid, unless it springs from the roots of individuality.

4. Everything that hinders the individual from fully developing his powers is thrust aside.

5. The saying ‘Each one of us must choose his hero in whose footsteps he toils up to Mount Olympus’ no longer holds true for us.

6. We allow no ideals to be forced upon us, we are convinced that in each of us, if only we probe deep enough into the very heart of our being, there dwells something noble, something worthy of development.

7. We no longer believe there is a norm of human life to which we must all strive to conform.

8. We regard the perfection of the whole as depending on the unique perfection of each single individual. We do not want to do what anyone else can do equally well.

9. No, our contribution to the development of the world, however trifling, must be something that, by reason of the uniqueness of our nature, we alone can offer.

10. Never have artists been less concerned about rules and norms in art than today.

11. Each one asserts the right to express, in the creations of his art, what is unique in him.

12. Just as there are playwrights who write in slang rather than conform to the standard diction grammar demands.

1. No better expression for these phenomena can be found than this, they result from the individual’s striving towards freedom, developed to its highest pitch.

2. We do not want to be dependent in any respect, and where dependence must be, we tolerate it only on condition it coincides with a vital interest of our individuality.”